From coffee forest to forest coffee

Ethiopia bears an important heritage: it is the birth place of coffee.

It is in kaffa region that lies wild coffee forest and birthplace of coffee around the city of Bonga and near the village of Makira Quabale.

Today wild forest coffee still exists in Bonga's Forest Reserve, which covers some 500 square kilometers, is among the last remaining subtropical moist forests in Ethiopia. Forest coffee is defined by the NGO Patnerships For Forests as:

"Coffee that grows naturally in primary forests that have not been disturbed or damaged by human interference."

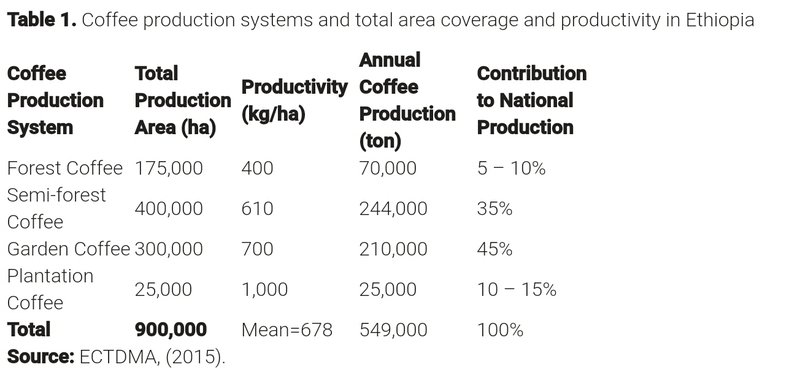

These lands are owned, virtually managed by the state and picking is only allowed for a limited period at the time of the harvest. It represents around 5% of to 10% of the total coffee production. Because of the lack of management, wild coffee trees have a low productivity. That's why they are little by little replaced by semi-forest coffee which represent now around 35% of the total coffee production.

Semi-forest coffee is defined as:

"Coffee that grows in forests that are semi-managed by humans (i.e. opening up canopies, clearing weeds etc.) but maintain a minimum of 50% canopy cover."

While two years ago I had the chance to see the original coffee forest hosting the Mother tree (the oldest living arabica coffee tree) and its surrounding lineage of wild coffee trees, this year we've been exploring coffee plantations of private owners with coffee trees, both wild and planted, growing under the shade of the forest.

We start the visit near Masha, a town in south-western Ethiopia, located in the Sheka forest in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples Region (SNNPR). This area is also famous for the production of organic white honey, which was for a long time the principal source of revenue for the local communities. Recently the government has also encouraged tea production by in areas previously unfarmed or where there was minimal agriculture.

At about 40km from Masha stands the farm of Heleanna Georgalis (Moplaco). 151 ha of land covered by forest and 145 ha dedicated to coffee.

False banana trees, an endemic plant from the banana family, are part of this ecosystem providing an ideal microclimate for coffee and preventing soil erosion thanks to its deep roots.

We're in the pic of the harvest. Trees are full of red cherries ready to be picked by the 180 people contracted for the season.

Enguday Eshetu Niferasha, the manager of the farm, welcomes us and shows us around the installations of the farm.

We start by walking along the lines of young and less young coffee trees. Enguday has the hard mission to take care of all these trees, to make sure they are well pruned to ensure a good productivity, to take care of the weeding regularly during the year to avoid apparition of diseases and to get rid of the potential infected trees if necessary.

Then we're heading to the drying station. Here the coffee follows the natural process, meaning that cherries are fermented and dried without firstly being pulped.

Enguday shows us the different methods : aerobic fermentation under the sun or under the shadow, maceration of coffee cherries in a steel container...

Everything is under control and the moisture level is regularly checked to know when the coffee is ready to be stored and to rest for a couple of month before being sent to the miller and sold.

No washed process at the moment in this farm as the fermentation tanks are still under construction. Maybe next year, we'll have the chance to taste a fully-washed coffee from Sheka forest!

After this brief introduction, we get the chance to see a bit more of the domain and observe the nice shapes of coffee trees under the shade of the forest, seeing by distance some black-and-white Colobus monkey. We quickly have to turn around though as a storm seem to come closer. When we arrive back to the farm, it's already late in the afternoon and we are observing the ritual of the end of the day.

In front of us, a long file of pickers waiting for their bags of cherries to be weight after being sorted to take out the unripe and overripe ones.

Afterwards, cherry floaters will be separated manually and put in a table apart. And then it's time for the workers to go back to their home. For those not living nearby the farm, they can take the truck chartered to pick them up in Masha in the morning and to bring them back at the end of the day.

It was a quick visit to the farm and even if we didn't have the chance to cup the coffee from Heleanna's farm, we now have a better understanding of the coffee production scheme and routine in Ethiopia.

Although not totally wild, semi-forest coffee benefits from an exceptional environment with a lively diverse fauna and flora.

Trying to improve the quality and productivity of the coffee, respecting the biodiversity with the introduction of natural compost, the preservation of organic methods farming combined with modern agricultural methods is not an easy task. Heleanna tries her best to do it in collaboration and for the development of the local community.

References:

- www.addisfortune.net/columns/precarious-fate-of-ethiopian-forest-coffee/

- www.coffeehabitat.com/2011/02/ethiopia-wild-forest-coffee/

- www.sacredland.org/sheka-forest-ethiopia/

- www.partnershipsforforests.com

Ethiopia

Ethiopia Colombia

Colombia Guatemala

Guatemala Indonesia

Indonesia Kenya

Kenya Mexico

Mexico Philippines

Philippines Tanzania

Tanzania Uganda

Uganda