Coffee in Colombia

Coffee in Colombia

Colombia is the third largest coffee producing country in the world. There is no other product more linked to the history and culture of the country than coffee.

The coffee sector is extremely important for the Colombian economy. It represents 22% of the country's agricultural GDP and the main source of income for more than 550,000 families. It is also the most exported product.

At the level of the occupied area, coffee cultivation occupies a very important place with 22 of the 32 departments of the country producing coffee. 96% of the producers are small and they have on average 1.3 hectares of coffee.

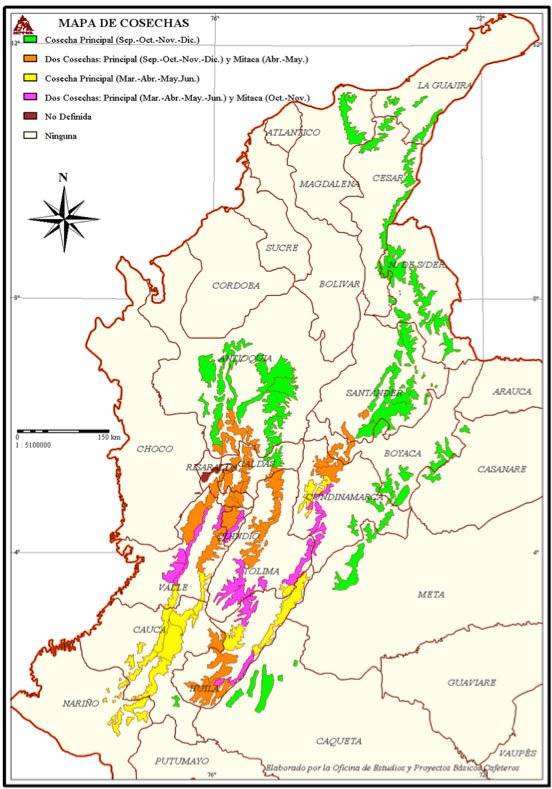

COFFEE GROWING REGIONS

The main coffee producing departments are Huila, Antioquia, Tolima, Caldas, Valle del Cauca, Cauca, Risaralda, Santander, Cundinamarca, Nariño, Quindío, Norte de Santander, Cesar, La Guajira, Magdalena, Boyacá, Meta, Casanare and Caquetá.

Colombia benefits from a great diversity of climate and a favorable topography to host several ecosystems. The specific geographical location of each Colombian coffee region determines particular conditions of water availability, temperature, solar radiation and wind regime. Thus it turns out that fresh coffee is harvested regularly throughout the country year-round.

In most coffee growing regions, the flowering period goes from January to March with a second one from July to September. The main harvest in these areas takes place between September and December. The secondary one called "mitaca" happens between April and June. The main harvest and that of mitaca can alternate in other regions according to their latitude.

VARIETIES

The main cultivated varieties are: Typica, Bourbon (yellow, red, pink, orange), Caturra (yellow and red), Maragogype, Pacamara, Castillo, Colombia, Marsellesa, Tabi. Recently, the Geisha variety - known for its high complexity and quality despite its low yield – has been introduced in an experimental way.

The National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia encourages the use of more productive hybrid varieties, resistant to diseases and climate change. There are important research centers in the country that are dedicated to study and improve all aspects related to the cultivation of coffee and its communities: Cenicafé between Manizales and Chinchina; Tecnicafé near Popayán, Cauca.

CUPPING PROFILE

Colombia is known for the production of soft, clean-cup coffee with relatively high acidity, balanced body, intense aroma and an excellent quality sensory profile.

However, from one region to another, coffee can offer different organoleptic profile. In the southern areas of the country for example, close to the equator, coffee is produced at a higher altitude and at temperatures that, without being extreme, are less elevated. The coffees produced in specific regions such as Nariño, Cauca, Huila or South Tolima have particular harvest cycles and usually make coffees with higher acidity.

In contrast, coffees produced in the North of the country - from regions such as the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the Serranía del Perijá or the Colombian departments of Casanare, Santander and North of Santander - have a different climate offer. They grow at lower altitudes and higher temperatures. Crops are also frequently protected from solar radiation by different levels of shade. A series of factors that modify the cupping profile: usually less acidity but a deeper body.

A BIT OF HISTORY

There are several versions telling the arrival of coffee in Colombia The oldest written testimony is attributed to the jesuit priest José Gumilla in the year 1730.

However, it was only a century later, in 1835, that the first commercial coffee production took place in the region of "Los Santanderes". The story tells that a priest named Francisco Romero put as a penance to the sinners sowing a coffee plant to atone for their sins. Thus coffee cultivation was expanded through penances all over the country. Even today you can hear this story from the producers.

Later one in 1870’s, the focus was put on exportation. At that time, coffee was considered a first-class national product dominating gold and tobacco. The first trigger was the decrease in the cost of transportation thanks to the development of the railroad in the country. It allowed to remove coffee areas from isolation and give a big boost to the growth of coffee exports. Thanks to that new infrastructure, the level of exports went from 17% in 1870 to 40% at the end of the 19th century.

At the beginning of the 20th century, with the colonization ere, the structure of the coffee property was drastically modified with the proliferation of small and medium properties rather than big domains. However, the export business remained in the hands of the haciendas and foreign firms. In 1930, ten firms were dominating the export trade and six of them were foreigners, accounting for 40% of the market. A structure and a distribution of power that is still relevant in the current coffee landscape, with more than 500,000 small producers contributing to 55% of the production without being able to live decently from coffee.

It is at this time that the National Federation of Coffee Growers was created (in 1927) to defend the interests of the peasants.

THE NATIONAL FEDERATION OF COFFEE GROWERS (FNC)

The FNC is a federative and democratic organization that represents the interests of approximately 523 thousand Colombian coffee families. Its objective is to "consolidate the productive and social development of the coffee families, guaranteeing the sustainability of coffee growing and the positioning of Colombian coffee as the best in the world."

The FNC acts as a regulatory body for the coffee market. It is a unique model in the world. It is entitled to manage, by delegated administration of the government, the National Coffee Fund, "a public treasury account permanently dedicated to the defense, protection and promotion of the Colombian coffee industry (...)"

The FNC makes a guarantee of purchase to many producers thanks to a system of regional cooperatives. This marketing system has 36 cooperatives, 492 points of purchase, 13 general warehouses that store, process and export coffee. The Federation also owns the world's largest coffee freeze drying company located in Chinchiná, in the historic coffee belt.

However, despite its important role in market regulation, the FNC is not exempt from any criticism. Throughout the years, decisions that seem to favor private interests and weaken the coffee sector have been questioned and are a cause of mistrust for small producers.

CHALLENGES FOR THE COFFEE INDUSTRY IN COLOMBIA

Critics of the National Federation of Coffee Growers

The National Federation of Coffee Growers is criticized for acting away from the coffee reality and the regional economic situation to favor a closed group of coffee growers and exporters. The destination and good management of the resources of the National Coffee Fund have also been questioned. Finally, the development of a strategy of productive change and modernization of the coffee field that did not take into account the logic, the knowledge of the producers and theenvironmental consequences, has been challenged.

An extreme concentration of the land ...

The process of land concentration is a structural problem in the country that is exacerbated by the lack of agrarian reform, causing higher levels of insecurity and violence in the countryside. The agrarian structure of Colombia has undergone a considerable transformation, from a stately landowner structure to the form of concentrated "modern" capitalist property, which accounts for between 40 and 70% of the most fertile lands directed towards the external market and with reduced use of the workforce.

... which contrasts with its excessive division

Curiously though, one can observe an excessive division of the land into very small properties. Small producers (many do not reach 2 ha) are exhausted, unproductive, hardly trained and unable to face the challenges of climate change by themselves.

Extreme poverty at stake

Many of the coffee farms correspond to a typical family farming model. Coffee remains the main income generator for the whole family despite the continuous fall in prices over the last four years, the loss of resistance of hybrid varieties to rust, increasing temperatures that favor the spread of diseases and parasites, increasing production costs (labor, fertilizers, fertilizers etc ...), the reality of a crop that still needs 60% of human labor (to pick coffee cherries on the hillsides where arabica grows), the lack of profitability in small land extensions... Bearing all these issues, coffee families are no longer able to live only of coffee and are often in risk of extreme poverty.

They have no choice but to diversify their crops (with bananas for instance), to find complementary jobs outside the farm or, in some cases, to abandon coffee to move to livestock or invest in tourism activities. There’s a clear example of this trend in the department of Quindío, in the famous "coffee belt". That region was one of the most productive in the past and if you can still find a bit of coffee there, most of them have turned into livestock farms or have become an attraction for many tourists passing through this area.

Invest in adequate infrastructure.

Colombia's coffee sector suffers from poor infrastructure in mountainous areas, especially in the departments of Cauca, Huila, Tolima and Nariño. Moving merchandise to a large city to sell coffee is the biggest challenge for some producers, as some areas can only be reach by motorcycle which drastically limits the transportable volume. And it seems that such isolated producers do not receive much help to improve the general state of the roads. There is a need for local and federal government support and initiatives on that specific issue.

" The Colombian must learn how to drink good coffee."

Improve consumption in the domestic market.

In Colombia, coffee is the most appreciated beverage in the country and represents 47% of beverage consumption. 90% of Colombians consider coffee as the national drink and 84% that coffee is the country's symbol in front of the world. Coffee is associated with a tradition of conviviality and 50% of consumers started drinking it with milk before 10 years old Then after 30, the tinto (filtered black coffee) becomes the queen drink. Many drink it with panela water, another star product of the country. Thus Colombia has a very interesting consumption potential. But then ... Why is most coffee produced for export?

First, because since the end of the 19th century, the coffee industry was directed towards exportation. Which means that the best coffee went out and the worst remained in the country for internal consumption. Colombians have become accustomed to drinking this bitter tinto sweetened with panela water. The Federation also comments that the average shopping basket in Colombia does not allow the consumption of high quality coffees normally exported. In addition, the country has been greatly affected by armed conflicts between the government, paramilitaries and drug traffickers that made many victims within the population. In the face of such a serious humanitary crisis, it is difficult to propose a gastronomic development plan and quality coffee education. That is why the director of the Café San Alberto company, Juan Pablo Villota, affirms that " the Colombian must learn how to drink good coffee."

However, the country is changing and with it, the trend of quality coffee. A middle class with better purchasing capacity has appeared in big cities over the past 10 years. This trend allows the development of specialized coffee shops whose objective is to make consumers aware of the wealth of Colombian coffee, its diversity from one region to another, so that they value the work of the producers behind. There is still a lot to do but there is a clear trend towards the quality of consumption and production of Colombian coffee.

FORCES OF COLOMBIAN COFFEE

The brand "Café de Colombia" and the figure of Juan Valdez

The beginnings of Juan Valdez were formed in 1959, when the Colombian Federation of Coffee Growers decided to make Colombian coffee known throughout the world through this famous character.

The world were meant to recognize the quality of Colombian coffee through Juan Valdez, his mule (Conchita) and the Andes mountains in the background. This branding strategy, which seeks to position a brand character, has served as an example in the world for its great effectiveness in raising awareness of an agricultural product.

Strong of this success, the FNC decided in 2002 to register a franchise and open their first Juan Valdez store at the El Dorado International Airport in the city of Bogotá. Since that year, Jaun Valdez stores have developped their presence in more than 14 countries in the world.

Geographical indication and designation of origin

Colombian coffee is a protected geographical indication, which was officially recognized by the European Union on September 27, 2007. The term Colombian Coffee is also a registered trademark and a Protected Designation of Origin. This is the result of a great work by the Federation to make Colombian Coffee recognized worldwide as high quality coffee.

Great diversity of sensory profile

From the North to the South of the country, Colombian coffees offer a rich and wide diversity of flavors due to multiple geographical, climatic and processing factors that impact the entire production chain, from seed to cup.

Focus on specialty coffee

If Colombia was always considered as a producer of high quality coffee, making of "Excelso" or "Supremo" true market references, the specialty coffee trend has revolutionized our perception of what good coffee has to be. There are now physical and sensory evaluation criteria that give the opportunity to other types of coffees, from other origins, to access the market of specialty quality coffees. In front of these new competitors, Colombia cannot simply rest on its laurels and take for granted what it had achieved as a third world producer in volume.

The coffee landscape also changed. If we used to talk traditionally about the coffee belt in reference to the departments of Caldas, Quindío and Risaralda, it’s been a few years already that the interest of buyers has turned south, in the departments of Valle de Cauca, Cauca, Huila and Nariño.

It should be noted that specialty coffee actors (producers, cooperatives, roasters) and research centers such as Tecnicafé invest time and money in process experiments - both fermentation and drying - to improve coffee quality, reduce costs of production, generate better performance and better payments.

These same actors are also ensuring the education of producers, especially the smallest and most isolated, so that they have a better understanding of the stages of the processes from seed to cup. The objective is to show them to the way to specialty market that offers a better added value and can help improving the quality of life of the producers.

Young people are also encouraged to work with coffeem thanks to this new wave. Specialized coffee shops now abound in big cities. In the field too, the youngest and more educated generation is encouraged to take over, recovering abandoned lands to maintain coffee tradition, implement good agricultural practices and support small producers with innovative projects.

REFERENCES

- Interview with the team of Caravela Coffee, Azahar Coffee, Invercafé, Flor de Apia, La Aurora (Manizales), La Meseta, La Venta Estate Coffee, Indestec, Tecnicafé, Coocentral

- ¿Como crear valor al café colombiano en Colombia? Trabajo de Grado por Thibault Chauvin

- Regiones cafeteras de Colombia

- Café de Colombia

- Federación de Cafeteros de Colombia

- La importancia del fondo nacional del café

- El colombiano debe aprender a tomar buen café

Ethiopia

Ethiopia Guatemala

Guatemala Indonesia

Indonesia Kenya

Kenya Mexico

Mexico Philippines

Philippines Tanzania

Tanzania Uganda

Uganda