Coffee in Indonesia

Coffee in Indonesia

Indonesia is geographically and climatologically well-suited for coffee plantations, near the equator and with numerous interior mountainous regions on its main islands, creating well-suited microclimates for the growth and production of coffee.

It is the fourth largest producer coffee of in the world and accounts for 7% of global coffee production with 10 millions of 60kg bags in 2017 (approximately 660,000 metric tons of coffee).

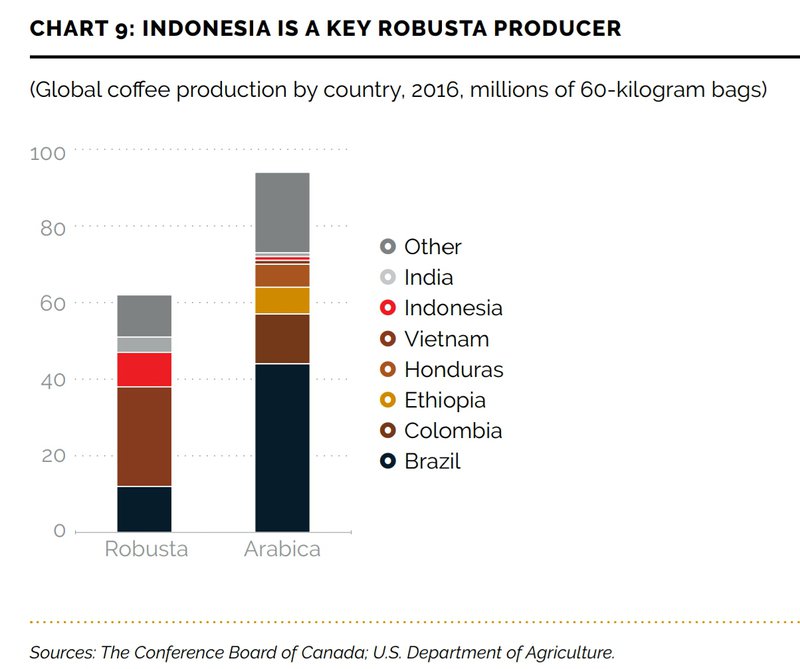

Robusta is the majority as it is more suitable for the low lands, high temperatures, high levels of humidity and significant rainfalls of the country. Its volume of production is six times the one of arabica and accounted for 14% of global production in 2016.

Currently, coffee is the country’s fourth most exported agri-food, following palm oil (49.2%), fish and crustaceans (8.5%), cocoa and cocoa preparations (4.2%).

Despite geographic and environmental factors that support Robusta production, there are more than 20 different varieties of Arabica coffee grown commercially in Indonesia. Considered as a finer product than the low standard robusta used for instant coffee preparation, arabica fetches higher prices on the global market.

This has led to farmers and the government favouring Arabica, representing today around 14% of the total production, compared to only 7% in 2000.

Of this total, it is estimated that 154,800 tons were slated for domestic consumption in the 2013/2014 financial year. Of the exports, 25% is arabica ; the remaining 75% is robusta.

COFFEE REGIONS

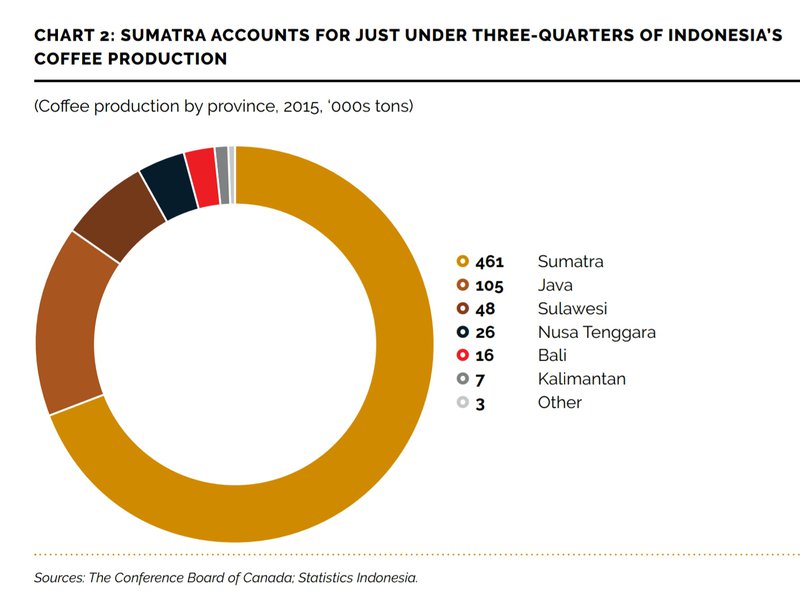

The main areas of robusta production are in South Sumatra (Lampung) and in East Java (Malang, Dampit).

Arabica coffee grows in the higher lands of North Sumatra (Aceh, Gayo, Mandheling, Lintong, Karo), East and West Java (Ijen, Bandung), South Sulawesi (Celebes, Toraja), Bali (Kintamani), Flores, Timor and Papua.

A BIT OF HISTORY

Coffee cultivation in Indonesia began in the late 1600s and early 1700s, in the early Dutch colonial period. The first seedlings were brought in the city of Batavia (Jakarta) on the island of Java. The plants grew, and in 1711 the first exports were sent from the port of Batavia to Europe by the Dutch East India Company, known by its Dutch initials VOC (Vereeningde Oost-Indische Company). Indonesia was the first place, outside of Arabia and Ethiopia, where coffee was widely cultivated.

At that time, the East Indies were the most important coffee supplier in the world during this period and it was only in the 1840s that they were eclipsed by Brazil.

By the mid-1870s the Dutch East Indies expanded arabica coffee growing areas in Sumatra, Bali, Sulawesi and Timor. In Sulawesi the coffee would have been planted around 1850. In North Sumatra highlands it was first grown near Lake Toba in 1888 and later on in 1924 in Gayo highlands (Aceh).

Coffee was also grown in East Indonesia - East Timor and Flores. Both of these islands were originally under Portuguese control and the coffee was also C. arabica, but from different root stocks.

In the late 1800, Dutch colonialists established large coffee plantations on the Ijen Plateau in eastern Java. However the coffee rust disease swept through Indonesia in the 1876, wiping out most of the Arabica Typica cultivar.

Robusta coffee (C. canephora) was introduced to East Java in 1900 as a substitute of arabica, especially at lower altitudes, where the rust was particularly devastating. It spreaded quickly across southern Sumatra (Lampung) during the 1920s, where production soon eclipsed Java. The region remains the most important producing region by volume today.

The arabica from North Sumatra is the most famous internationally. Not only because the productivity and level of exports from this region is the most important, but also because of its distinctive and tunique giling basah (wet hulling) processing technique.

Following this method, the beans in parchment are hulled with a level of 30-35% of humidity (instead of 12-14% normally). The process was introduced to accelerate the process of drying in regions counting with heavy rainfalls and high level of humidity.

At the green bean stage, coffee from this area has a distinctive bluish colour, which is attributed to processing method and lack of iron in the soil. It is also said to give a particular cupping profile with cocoa, tobacco, smoke, earth and cedar wood.

VARIETIES

Today there are more than 20 varieties of arabica growing in Indonesia. They fall into six main categories:

- Typica – this is the original cultivar introduced by the Dutch. Much of the Typica was lost in the late 1880s, when the coffee leaf rust swept through Indonesia. However, both the Bergandal and Sidikalang varieties of Typica can still be found in Sumatra, especially at higher altitudes.

- Hibrido de Timor (HDT) – This variety, which is also called "Tim Tim", is a natural cross between Arabica and Robusta. This variety originated likely from a single coffee tree planted in 1917–18 or 1926. The HDT was planted in Aceh in 1979.

- Linie S – This is a group of varieties was originally developed in India, from the Bourbon cultivar. The most common are S-288 and S-795, which are found in Lintong, Aceh, Flores and other areas.

- Ethiopian lines – These include Rambung and Abyssinia, which were brought to Java in 1928. Since then, they have been brought to Aceh as well. Another group of Ethiopian varieties found in Sumatra are called "USDA", after an American project that brought them to Indonesia in the 1950s.

- Caturra cultivars – Caturra is a mutation of Bourbon coffee, which originated in Brazil.

- Mundo Novo – A natural cross between Typica ad Bourbon originally discovered in Brazil. Seeds coming from Thailand have recently been introduced in the high lands of Mount Puntang, district of Bandung, West Java.

- Catimor lines – This cross between arabica and robusta has a reputation for poor flavour. However, there are numerous types of Catimor, including one that farmers have named "Ateng-Jaluk". On-going research in Aceh has revealed locally adapted Catimor varieties with excellent cup characteristics.

CHALLENGES FOR THE COFFEE INDUSTRY IN INDONESIA

A fragmented sector

90% of Indonesian coffee production comes from small farmers of less than 1 ha. The production sector is very fragmented with still a limited number of cooperatives or farmer groups. Most of the farmers usually sell directly their cherries to some so-called collectors that will take care of the process and then sell the beans to exporters. Some farmers do make a manual home-process but only for a very limited quantity as they don't have the sufficient facilities and equipment to deal with higher volume. As a result, it is difficult to ensure a constant quality and level of productivity.

Lack of productivity

On that issues, all the actors of the value chain agree. Producers, cooperatives, exporters, coffee experts, government, NGOs... All report the problem of the low yield and accuse mainly the climate factors (extreme draughts and extreme rains affect the flowering and ripening of the coffee cherries), the lack of pruning and of agricultural inputs.

The average annual yield is about 570kg/hectare, a stagnant level since 2005. Some farmers more dedicated to coffee farming than other crops can reach up to 800kg/ha. Still pretty far from their neighbour champion of low quality robusta productivity that produce currently up to 2400kg/ha - Vietnam.

Some important actors of the industry have implemented programmes of action on the field to improve the producivity of robusta coffee through the training of the farmers to Good Agricultural Practices (GAP). This includes education on erosion control, cofee nutrition, composting, weeding, pruning, seedling, shade management, pest and disease control, injection of fertilisers and other agricultural inputs (preferably not chemicals). Access to financing, structuration of the sector and investment in facilities for post-harvesting are usually also part of these programmes.

Broaden Access to Finance

The sector’s low productivity leaves farmers with limited income levels and cash flow, which consequently inhibits investment in the technologies, facilities and equipment that could help to resolve the productivity problem. Ensuring proper access to finance and educating farmers on the potential benefits of investing would help to support the sector.

Improve collaboration between small farmers

As the sector is little structured, there's also a lack of collaboration between the farmers. There are initiatives, still marginal though to enhance collaboration through the development of small cooperatives all over the country. This will take time but this form of collective management could offer the financial capacity to invest in adequate and qualitative machinery or other value-adding products to improve quality and productivity.

Invest on adequate infrastructures

Indonesia’s coffee sector is highly reliant on both road and water transportation. Its global competitiveness is negatively impacted by the country’s relatively underdeveloped port and road infrastructure that firms use to move inputs into the country and ship cofee out to their buyers. There's a need for support and initiatives of the government in that specific issue

STRENGTHS OF INDONESIAN COFFEE

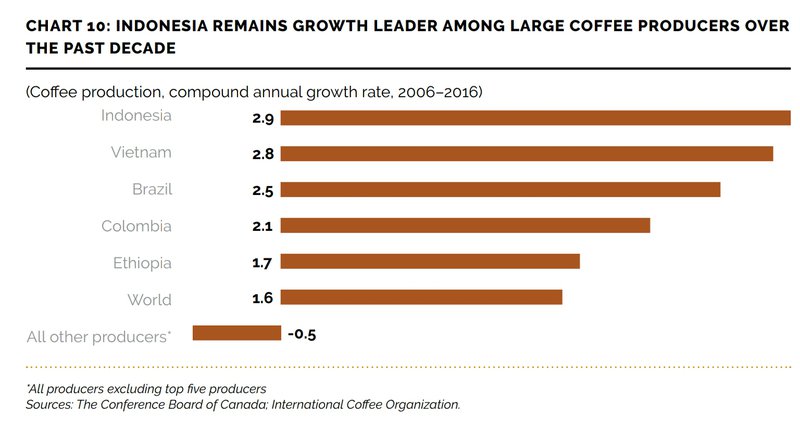

The country’s exceptional production growth over the past decade. None of the world’s other five largest coffee producers have seen stronger gains than Indonesia over the past decade.

Domestic Consumption

While cofee exports have increased by an annual average of 5.5% since 2000, domestic coffee consumption has increased by an even-higher 6.9% a year on average. This is due firstly to the increasing population (from 210 million people in 2000 to around 260 million today).

Secondly, the internal consuming is growing, following the rising of a middle class with better capacity of absorbing the coffee production. Coffee shops have popped up all over Indonesia offering a large variety of indonesian origins (mainly of arabica coffee) and different kind of brewing methods.

Export capacity

Foreign markets still account for the greater share of Indonesian cofee production. Over the past five years, Indonesian producers have exported an average of 2 kg of coffee for every kilogram consumed domestically.

REFERENCES

- Coffee map: cartoffel.com/portfolio/indonesia-coffee-growing-regions/

- Giling basah : cremacoffeegarage.com.au/blog/crema-trekkers-explore-indonesia-blue-bianca

- en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coffee_production_in_Indonesia

- espressocoffeeguide.com/gourmet-coffee/asian-indonesian-and-pacific-coffees/indonesia-coffee/#sumatra-coffee

- An Analysis of the Global Value Chain for Indonesian Cofee Exports, The Conference Board of Canada, 2018

Colombia

Colombia Ethiopia

Ethiopia Guatemala

Guatemala Kenya

Kenya Mexico

Mexico Philippines

Philippines Tanzania

Tanzania Uganda

Uganda